Saturday, July 27, 2013

Musings on Anger

Most of the time, I'm okay with that. I think it's a good thing. It helps keep me wary so that I don't fall for similar traps and fictions. It motivates me to spread the word--or the anti-word, I suppose. It helps remind me of what my life used to be, what it is now, and what I want it to become.

But it would be nice, I think, to eventually have peace. I don't want to be angry forever.

But I can't just stop being mad. Every time I interact with my family, I'm reminded of the sources of my anger. Every strained conversation, every time one of us inadvertently trips over the elephant in the room, every lie I tell to spare my mother the "horrible" truth, every time I bite my tongue to keep from screaming at them, from admonishing them to wake up and be reasonable...I remember my anger. It's not something I can let go of.

It would be easier if my family were more willing to accept my lifestyle. To be fair, I haven't given them much of a chance to. As best I can gauge it, if I were to tell them that I live with my girlfriend, that I swear when I'm pissed (and even when I'm not), that I watch porn and listen to death metal and drink coffee, I'd face a variety of unpleasant circumstances. My dad would be depressed but continue prodding me with unsolicited offers for counsel and advice. My mom would be flat-out heartbroken and probably a little scared of me for a while. My oldest sister would be angry--she'd express shock that I could act so foolishly and she'd lash out a little. My middle sister would perhaps calmly bring the problem up once and never speak of it again. And my youngest sister, with whom I used to share a close relationship, would leave me those horrible voicemails in her distant, plaintive and pitiable style telling me that she doesn't understand but that she misses her little brother.

And I'd feel so guilty.

And the guilt would make me angry all over again, because I shouldn't have to feel guilty. Leaving the church was the best decision I have ever made in my entire life--period. I know it was the right thing to do--period. I'm so much happier now than I was before--period.

But all the periods are becoming semicolons. It was the best decision I have ever made in my entire life, semicolon, it's had some of the worst consequences of any decision I have ever made. I know it was the right thing to do, semicolon, I can't convince my own family of that. I'm so much happier now than I was before, semicolon, but so much still hurts because I had to take the journey alone.

I wish I could talk freely on any subject with my family. I wish I could show my parents the apartment I've had for the last two years, since it's only ten minutes from their house. But then they'd see all my girlfriend's stuff and the bed we share. I wish I could discuss entertainment without constantly checking myself to make sure I'm not talking about something they'd disapprove of. If I can't remember if a movie was rated R, I better not tell them about it. Hell, I'd love to tell them about my novel and to hear what they think of it--if I knew they wouldn't be horrified by the language and the casual references to sex. I can't even tell them half of the stupid stuff that happens at work without mentally combing through the stories first to make sure they're still amusing to a conservative Mormon audience. It doesn't feel like a family when I feel the need to censor my own existence for their consumption. I do it to avoid the confrontation, to avoid the judgment, to avoid the worry, and to avoid the frustratingly self-righteous pity. What else am I supposed to do?

Yeah, all that makes me angry. The church, by its design, has manipulated my family into turning on me. There's no sense of "well, Alex is happy, and he's still a good person, so we're happy for him" without the sense of loss and disapproval. In his emails, my dad may tell me that he's proud of me, but it rings hollow when I consider the fact that he firmly believes that because of my choices I won't be with the rest of them in the afterlife. You can't really be happy for someone if you're convinced he's destroying himself. You can't be proud of someone for doing what, in your eyes, equates to burying his head in the sand. You can't have a normal, healthy familial relationship with someone you think has squandered the gift of life and needs to be fixed. You can't really be a family when differences of eternal gravitas have built walls between you. Can you?

The situation sucks. I know I'm not the only one in this situation. And I know my case is far from the worst of its kind. But there's plenty to be pissed about.

The only thing I can think of that could ever alleviate that anger is my family leaving the church. At best, that's a long shot. I'd like to make it happen--another long shot. If I were ever successful, the shock would be pretty hard on some of them--my mom in particular. I'd feel pretty guilty about that too.

I haven't tried to get any of them to leave, except for a few little jabs at my dad here and there. I think overtly campaigning for their apostasy without provocation would make me just as self-righteous as some of my least favorite Mormons--it would be considering my own belief that no one should follow a false religion to be a higher cause than whatever my family wants for themselves. If they find meaning in their existence, regardless of whether their faith is misplaced, who am I to discount that?

So I guess I'll have to wait patiently, always swarmed with reminders of my smoldering wrath, until one of them sends me an email asking to talk about the church. Then maybe I'll start trying to tear down a faith that's already wavering. Maybe.

My plan is doomed to failure. I may always be angry. But at least I'll feel like I'm doing the right thing.

Friday, July 26, 2013

Home Teaching Sucks

The first "family" that my dad and I were assigned to home teach was an ancient woman who lived alone. She had limited mobility but insisted on living in her house for as long as possible. She was sweet and funny and the whole ward loved her--seriously, I don't think anybody could have hated that woman. My dad and I did some occasional yard work for her in addition to our monthly visits. When it was my turn to give the lesson during our visits, she would listen attentively and offer a few helpful comments, sometimes going off on one of her famous stories from her childhood in Sweden. But I always got the feeling that she was humoring me. My dad was the expert home teacher, the scriptorian, the spiritual giant, and I was the trainee. She patiently allowed me to do my thing so that I could learn to become like my dad. I often felt silly and out of place, probably due to my sense of inferiority more than anything else. But this sheepish ministry was probably the best time I ever had home teaching.

Thursday, July 25, 2013

Mosiah 9: Zeniff's an Idiot

Skipping the Good Parts

In the first few verses, Zeniff glosses over a lot of exposition that sounds like it really doesn't deserve to be exposition. Here's what happens:

- Zeniff is sent to spy on the Lamanites to aid the Nephite army in destroying them

- Zeniff sees good things in the Lamanites and argues in favor of peace

- Zeniff is ordered to be executed, but is saved by a violent rescue

- Two factions of the army fought against each other with family members on opposing sides

- Zeniff's half is defeated but he survives, vowing to reclaim the land of his fathers

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

Mosiah 8: The Mystery of the Jaredites

The Vanishing Jaredite Battlefield

The characters—I mean, the historical figures—in this chapter don't know it yet, but the gold plates they found contain the story of the Jaredites, an earlier transplanted-Israelite-American-settlement. Verse 8 describes the location in which these plates were found:

...a land which was covered with bones of men, and of beasts, and was also covered with ruins of buildings of every kind...a land which had been peopled with a people who were as numerous as the hosts of Israel.This is hardly my most original point, but the commonly-posed question is fair—where are all those bones? In Ether, upwards of two million Jaredites were killed in battle. That's a lot of corpses and a lot of weaponry. That's a lot of people who used to live in homes and cities. That's a hell of a lot of archaeological evidence to simply not turn up. At over two million, the Jaredites had a population that rivaled the expanse of the Mayans and the Aztecs and maybe even the Incas. There is plentiful evidence of those nations. Why are there no Jaredite ruins—especially considering the Book of Mormon explicitly states that all the archaeological evidence we would ever need was there...at one point?

Limhi (n): gullible person

Limhi is so dumb. I just can't get over it.

Let's say you're a king (you know, hypothetically). And let's say a bunch of your subjects find a ruined civilization and massive battlefields strewn with skeletons. And let's say these subjects bring you a book they found among the wreckage. And let's also say that you know a guy who knows a guy who can probably figure out what the book says. What's your first reaction?

If you said, "wet myself with excitement over the enigmatic contents of the book and praise God!" then I have some bad news for you—you're probably a Limhi:

Doubtless a great mystery is contained within these plates, and these interpreters were doubtless prepared for the purpose of unfolding all such mysteries to the children of men.

O how marvelous are the works of the Lord...Look, Limhi: I get that you want to know what's written on those plates, but nothing you just said is "doubtless." It could be that the plates simply contain the boring genealogy of the destroyed civilization and no great mysteries. It could be that the fact that King Mosiah can probably translate the records is nothing more than coincidence. And let's not forget that you're giddy as a schoolgirl over some writings found in a place where a few million people slaughtered each other. Have a little respect for the dead.

Limhi is willing to believe pretty much anything. Doubtlessly his name must have become ancient American slang for a stupid person (see what I did there?). I'm picturing a Lamanite child coming home from school in tears because the other kids called him a "Limhi-butt" and a "curelom-face."

Joseph Smith Pulls a Melville—or Maybe a Wilde

In verses 13 through 18, the narrative goes off on a bit of a tangent about seers, prophets and revelators (but mostly seers). The definitions of each of the terms are pretty unimportant and certainly not central to our salvation, but for some reason they were laboriously etched into sheets of metal to be read in our day.

To be honest, it reminded me of that chapter in Moby-Dick when Melville goes on and on about the different kinds of whales or the chapter in The Picture of Dorian Gray when Wilde rambles about his character's new fascination with different kinds of fabrics and perfumes. Joseph Smith's tangent pales in comparison, as it's only a few verses, but it shares the same characteristic—the level of detail does not match the level of significance.

By the way, all seers are prophets but not all prophets are seers. It's kind of like a square-and-rectangle thing. In case you were wondering. And I'm sure you weren't.

Sunday, July 21, 2013

Mosiah 7: Limhi's an Idiot

Meaningless Numeric Symbolism

Joseph Smith takes care to mention twice (in verse 4 and verse 5) that Ammon's search party wandered in the wilderness for forty days. Forty. It had to be forty.

Forty is kind of a significant Biblical number. Jesus fasted for forty days. Noah got rained on for forty days. Moses was on Mount Sinai for forty days. The Israelites wandered for forty years after leaving Egypt. And so on and so forth. Why did Ammon have to get lost for forty days exactly?

Because it served the purpose of the author—to create as many contrived connections to the Bible as possible in the hopes of boosting the credibility of his hack work.

Limhi Lets Himself Get Conned

King Limhi, who reigns over the Nephites in the Land of Lehi-Nephi but under the thumb of the conquering Lamanites, has, in only one chapter, shot to the very top of my list of dumbest Book of Mormon characters. Observe what happens when he tries to question Ammon after Ammon is captured by the guards:

And [Limhi] said unto [Ammon and three of his friends]: Behold, I am Limhi, the son of Noah, who was the son of Zeniff, who came up out of the land of Zarahemla to inherit this land, which was the land of their fathers, who was made a king by the voice of the people.

...And now, when Ammon saw that he was permitted to speak, he went forth and bowed himself before the king; and rising again he said: O king, I am very thankful before God this day that I am yet alive, and am permitted to speak; and I will endeavor to speak with boldness;

For I am assured that if ye had known me ye would not have suffered that I should have worn these bands. For I am Ammon, and am a descendent of Zarahemla, and have come up out of the land of Zarahemla to inquire concerning our brethren, whom Zeniff brought up out of that land.

And now, it came to pass that after Limhi had heard the words of Ammon, he was exceedingly glad, and said: Now I know of a surety that my brethren who were in the land of Zarahemla are yet alive. And now, I will rejoice; and on the morrow I will cause that my people shall rejoice also.Let's summarize:

- Limhi introduces himself and includes irrelevant background information about where he and his ancestors came from.

- Ammon responds by introducing himself as a friendly visitor, reciting a history that aligns with Limhi's previously shared background.

- Despite the fact that Ammon could have simply made his identity up using all the information Limhi had given him earlier, Limhi decides that Ammon is legit and proclaims a celebration in honor of the survival of the other half of the Nephites.

Limhi's an idiot.

Limhi Gets His Wires Crossed

Limhi's behavior continues to astonish me in verse 15 when he voices his hopes that Ammon and company will free his people from Lamanite bondage (which seems to mean political subservience and heavy taxation):

And now, behold, our brethren will deliver us out of our bondage, or out of the hands of the Lamanites, and we will be their slaves; for it is better that we be slaves to the Nephites than to pay tribute to the king of the Lamanites.Get a grip, Limhi! Listen to what you're saying! It doesn't make any sense!

You'd rather be a slave to the Nephites than a satellite nation of the Lamanites? Because paying taxes to an evil king is worse than abandoning your freedom and your property? I mean, Hitler did horrible things to the Jews, but at least his tax rates were reasonable, right? I don't care if the Lamanites were evil and the Nephites were good—slavery is never more desirable than some hefty taxes, no matter who you're paying the taxes to. And what the hell kind of ruler volunteers his entire nation for slavery?

Why did the people not overthrow this imbecile and appoint themselves a king with some brain function?

Witnessing a Convoluted Sentence

To top it off, Limhi is also an atrocious orator—which is tragic, considering that most of what I've seen the Book of Mormon kings do so far is fight wars, tell people to plant food, and give really long speeches. I don't know how Limhi has done with farming edicts, but he's clearly wimped out on war since his people remain under the Lamanites' thumb. And as far as public speaking goes, he's pretty terrible. Observe:

And ye are all witnesses this day, that Zeniff, who was made king over this people, he being over-zealous to inherit the land of his fathers, therefore being deceived by the cunning and craftiness of king Laman, who having entered into a treaty with king Zeniff, and having yielded up into his hands the possessions of a part of the land, or even the city of Lehi-Nephi, and the city of Shilom; and the land round about—

And all this he did, for the sole purpose of bringing this people into subjection or into bondage. And behold, we at this time do pay tribute to the king of the Lamanites, to the amount of one half of our corn, and our barley, and even all our grain of every kind, and one half of the increase of our flocks and our herds; and even one half of all we have or possess the king of the Lamanites doth exact of us, or our lives.He starts off talking about how everyone is a witness to something Zeniff has done--and then he reviews a few things, qualifies a few things, gets needlessly specific about a few things...and never comes back to his original thought. We're witnessing that Zeniff what? WHAT ARE WE WITNESSING?! Limhi blows through six commas, a semicolon and an em dash like they're suburban stop signs before moving on to his next thought instead of finishing his first one. This is the most correct book on the face of the Earth?

There's also the minor detail that these people are not witnesses to anything about Zeniff, because Zeniff was Limhi's grandfather. Zeniff has been dead for a long time and it seems pretty silly to tell people that today they are witnessing what amounts to a review of historical facts. How exactly can one be expected to be a witness of something that happened before one was born?

Have I mentioned that Limhi's an idiot?

God's Petulant Favoritism

Despite what the Book of Mormon says, this god is not a just god. I know I've harped on this point before, but it bears mentioning again. The Lamanites, according to Limhi, are wicked and abominable. They've killed countless Nephites and even killed the prophet, but they are under no threat of destruction. To the Nephites, however, God says this:

I will not succor my people in the day of their transgression; but I will hedge up their ways that they prosper not; and their doings shall be as a stumbling block before them.God doesn't just stop fighting the Nephites' battles when they sin—he goes out of his way to hinder their progress. Being God's favorite comes at a high price.

The more I read about God in the Book of Mormon, the more he seems like some weird hybrid of a petulant child and an abusive parent.

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

My Ex-Mormon Manifesto

I think one of the only things that I truly miss about believing in Mormonism is the sense that everything about existence has been carefully planned and been ascribed meaning by our loving creator.

I didn't know it at the time, but as a member of the church, I was miserable. I had few friends. I felt suffocated by my schoolwork and my mounting commitments to the church. I loathed my own inability to measure up to church standards and despised the hypocrisy of my appearing to measure up. I was told that the church makes me happy, so despite the miseries of my daily life, I kind of assumed that my peers were more miserable.

But beyond that, I believed that all my suffering had a purpose and was part of a lifelong crescendo to the ultimate payoff. My afflictions would be but a small moment and all I needed to do was put my head down, suffer well, and do my best to keep the faith--and someday all of it would be worth it.

I miss that sometimes.

Now, as a decidedly indifferent agnostic, I don't have any assurances--false or otherwise--that any of my torturous experiences has any value. There is no inherent meaning to my suffering. This is the kind of thing people used to talk about in testimony meetings: life without the gospel is depressing. The reasoning made sense to me at the time, but now it reeks of a willful refusal to confront an uncomfortable possibility.

As nice as it would be to have a hope for a glorious eternal recompense for life's varied displeasures, I think it's better not to have it. On a purely conceptual, philosophical level, life may indeed be more depressing without the gospel. But in daily practice, I've traded an irrational self-loathing due to failure to meet an unattainable standard for a rational self-motivation due to not measuring up to my own more reasonable goals.

What I want from life is to be significant. I've always wanted that--I think most people do. I want to make a positive impact on the world. I want to write the next great American novel. I want to make people think and make countless griping high school seniors write papers about me. I want my life to have significance long after it's over.

Stripped of my belief that my life has intrinsic meaning, I feel much more motivated to achieve those things. Believing this life is literally all I have may be depressing, but I think it makes me more likely to leave a positive mark on the world.

And I think that's a good thing.

Friday, July 12, 2013

Shameless Self-Promotion

No, it's not a scathing memoir about the church's wackiness, like The Passion of the Raptor Jesus. Nor is it a thought-provoking chronicle of an LDS mission, like Heaven Up Here. In fact, it has pretty much nothing to do with Mormonism at all, which makes the self-promotion all the more shameless.

It's a novel. It follows the life of a kind-of-down-on-his-luck community college student in his attempts to find success, happiness, love and sex. It took me several years of tinkering to complete it and I'm proud of the finished product. My friends seem to think it's pretty funny and most of them have healthy senses of humor, so they could be right!

I guess the only ex-Mormon-blog-related point I could make here is that, because of the language and the sexual themes, I could never have written something like this as a faithful member of the church. One more reason why leaving was a good call.

Anyway, if you have a few extra bucks and a free afternoon sometime, I hope you'll check it out. Thanks!

The Weather Man on Amazon.com

Sunday, July 7, 2013

Donation, Schmonation

It's a big church built almost a hundred years ago on the site of the historical park. It had a pretty big pipe organ with ridiculously intricate hand-carved pipes and a whole bunch of patriotic-themed stained glass windows. One set of windows even depicted major events in the life of George Washington. It was pretty cool-looking and the guide there was knowledgeable, friendly, and seemed like a nice guy.

He mentioned that the building was a privately owned Episcopalian chapel for a local congregation, and therefore not the beneficiary of national park funding. He briefly invited us to leave donations in one of the donation boxes for the building's upkeep and preservation.

I didn't donate. Maybe I should have. I'm not really into Episcopalians or chapels, but I do care about history.

What impressed and surprised me, however, was that, as we were on our way out, my mom stuffed a five dollar bill in one of the donation bins. My dad was looking up at the stained glass windows at the time and I'm pretty sure he didn't see it. But as he walked out, I watched him slip what I'm pretty sure was a ten into the same bin.

Either I misunderstood my parents' stance on donations when I was little, or their stance is evolving. I didn't expect them to contribute because the only organization they trusted to distribute funds ethically and usefully is the church. Apparently I misjudged.

I was actually kind of proud of them for donating. It's useful sometimes to keep my post-Mormon ego in check. I may think I'm right and they're wrong, but they're still better people than I am in a lot of ways. They have a lot more money than I do, but there's no reason I couldn't have spared a couple of bucks. Believing in something that's true (or avoiding belief in something that's false) is far less important than being generous and trying to improve the world around you.

Mormon or not, they have me beat there.

Saturday, July 6, 2013

Mosiah 6: Nephite Politics

Holding Fast and Taking Names

At the conclusion of his sermon, King Benjamin "thought it was expedient" to record the names of all the people who had decided to make a covenant with God. According to verse 2, every adult had agreed to make the covenant.

This is dumb—for two reasons. First, come on, Joseph. Again with the entire societies functioning as a hive mind thing? Second, assuming this is an accurate record of historical events, of course so many agreed to the covenant. If you're going to run around like Big Brother taking names of the people who have decided not to be godless sinners, people are going to lie so that their government and their neighbors don't look down on them and treat them differently. Since the tide of public opinion was clearly swaying toward religiosity, it should be no surprise that so many people went along with it. You can sign your name to guarantee your safety because they can't prove you didn't mean it.

A One-Party System

The fact that the Kingship was both a governmental and a spiritual office combined with the fact that the entire society had committed their lives to God and dwelt with "no contention...for the space of three years" (verse 7) makes me think that the political landscape of the ancient Americas was pretty boring.

Hey, I'm going to vote for Mosiah again this year because he's running unopposed and he's the king anyway so we don't get to vote for him and also he's ordained of God so campaigning against him is kind of a sin. But, if anything, I guess he gets my continued stamp of approval this year. Just like last year. And next year. And the year after that.

That's not very American. The LDS romance with the US Constitution and the democratic process is not something they got from their foremost book of scripture.

Mosiah: Survival Expert

The last verse of the chapter relates this oddity:

And king Mosiah did cause his people that they should till the earth. And he also, himself, did till the earth, that thereby...Wait, back up. "Mosiah did cause his people" to cultivate farmland? Seriously? It's been four hundred and seventy-six years since Lehi left Jerusalem and these people still need their king to tell them to plant crops? They must have been really hungry, foraging for nuts and berries in the woods for all those centuries until Mosiah came up with the revolutionary idea to plant their own food.

Friday, July 5, 2013

Thursday, July 4, 2013

My Musical Exit Story

So let's begin at the beginning.

When I was really little, my understanding of music was limited to church hymns (which I didn't much like as a child) and Disney songs. The Little Mermaid was among my favorite movies. On the rare occasion that my siblings and I put music on the stereo, the most popular choice was one of the Greatest Disney Songs compilations we had. Thus, one of my favorite songs when I was little was "The Ugly Bug Ball."

As fate would have it, the oldies station failed only a couple of weeks after I started listening to it. One day, when I tuned my radio to the usual station, it was suddenly classic rock. I tried to find an oldies station to replace it, but, having no luck, I returned to the classic rock station. I figured "classic rock" meant it was still old music, so it probably wasn't evil like the satanic metal music they make today.

To my surprise, I learned that classic rock was actually pretty freakin' awesome. And there were so many artists. I'd stumbled across a treasure trove of musical knowledge to unlock. I listened ravenously for a while, and when that wasn't enough, I started using my parents' tape deck to record of the radio and make my own mixtapes so I didn't have to listen to the stuff I liked less. I discovered Led Zeppelin, Billy Joel, the Who, REO Speedwagon, Kansas, and countless others. Not all of it was great, but enough of it was good enough to keep me hungrily interested.

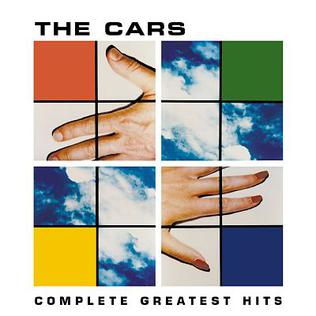

I began looking up some of these bands on the internet to learn more about them. I found a bunch of fan sites for my favorite band. I used my parents' terrible internet connection to stream a Yahoo! Music radio station for my favorite band. And, sometime around my freshman year of high school, I became aware of a new compilation CD of my favorite band. And that's when I tagged along with my mom to Wal-Mart specifically so I could buy my very first compact disc:

Fueled by my discovery of progressive music and spurred by my twelfth grade English teacher's frequent lectures on the nature of literature and art, I tried to explore as much music as I could, searching for art in music--searching for beautiful sounds that defied label or description, that connected with the emotional fibers of the listener and made philosophical statements instead of just money. It was during this high-brow phase that I found Porcupine Tree.

I'd returned to BYU for my second year instead of going on a mission, and I was entering my almost two-year-period of doubt before I actually left the church. I was confused and angry. Dream Theater and the heavy metal helped me on the anger side, but I didn't have much music to match my confusion. When I found Porcupine Tree, though, I was struck with the band's variety despite its nearly ever-present melancholy. It was a melancholy that I felt I understood and could connect with. When Fear of a Blank Planet came out, that album's depiction of a disconnect between father and son and its bleak atmosphere brought me to tears. The album, despite its frequent criticism of a pill-popping, desensitized generation that I didn't consider myself a part of, had so many moments that felt like they'd been written specifically for me.

It's still my favorite album of all time. It's a masterpiece. Even though I'm in a much different emotional mindset these days, Fear of a Blank Planet still evokes that regretful sadness and still packs the same punch. It's much more musically, lyrically and emotionally complex than Disney or Colin Raye--and it's also something I doubt I'd have ever listened to if I'd remained firm in the faith.

Shortly after I stopped attending church and told my parents I no longer believed, I met my girlfriend. She helped me move out and move on with my life. I told her once about how perfectly Porcupine Tree captured the way I felt about her impact on my life. And because of that conversation, "The Rest Will Flow" has kind of become our song.

So here's to good music. And here's to ignoring the religion that taught us not to find it.

Wednesday, July 3, 2013

Mosiah 5: Mass Conversion

One More for the List of Things That Just Plain Don't Happen

So apparently, following his address, Benjamin put some feelers out among his peeps to see if they bought all that horrible doctrine of threats and self-flagellation. Joseph Smith would have us believe that the people reacted this way:

And they all cried with one voice, saying: Yea, we believe all the words which thou has spoken unto us; and also, we know of their surety and truth, because of the Spirit of the Lord, Ominipotent, which has wrought a mighty change in us, or in our hearts, that we have no more disposition to do evil, but to do good continually....and so on and so forth for another three verses. This, of course, is completely unrealistic. People do not behave this way.

When is the last time in recorded history that an entire society was swayed to a particular belief or course of action instantly, unanimously, and passionately based on one address from one authority figure? There are always minority opinions, rebels and dissenters—even when one side should be obviously correct and the other side should be obviously wrong.

But this will be far from Joseph Smith's last mistake along these lines.

Spiritual Incest

Prepare for your mind to be blown by the implication made in verse 7:

And now, because of the covenant which ye have made ye shall be called the children of Christ, his sons, and his daughters; for behold, this day he hath spiritually begotten you; for ye say that your hearts are changed through faith on his name; therefore, ye are born of him and have become his sons and his daughters.King Benjamin's people, then, have become the children of their older brother. They have been begotten by the first begotten of the guy who already begat them. That's pretty messed up.

So it's not actually incest, of course, but it's more evidence that Joseph Smith was just making this crap up as he went along. It's too bad that he predated Tolkien, because he could have learned a lot from that guy when it came to planning out ridiculous mythology while avoiding continuity errors and plot holes.

Smith hadn't really decided on how the whole God/Jesus thing was going to break down yet, I guess. (In ten chapters, he's going to take a crack at parsing their differences and their relationship and he's going to fail miserably.) Because if he'd hammered out the whole spirit-children-war-in-heaven-older-brothers stuff, then this verse would have been way too strange to be worded this way. There are plenty of options for making the same point without getting entangled in weird celestial familial octopuses.

Pearls of Wisdom

Verse 10 made me chuckle:

...whosoever shall not take upon him the name of Christ must be called by some other name

For how knoweth a man the master who he has not served, and who is a stranger unto him, and is far from the thoughts and intents of his heart?