A few weeks ago, my family and I visited Valley Forge. While there, we visited the Washington Memorial Chapel.

It's a big church built almost a hundred years ago on the site of the historical park. It had a pretty big pipe organ with ridiculously intricate hand-carved pipes and a whole bunch of patriotic-themed stained glass windows. One set of windows even depicted major events in the life of George Washington. It was pretty cool-looking and the guide there was knowledgeable, friendly, and seemed like a nice guy.

He mentioned that the building was a privately owned Episcopalian chapel for a local congregation, and therefore not the beneficiary of national park funding. He briefly invited us to leave donations in one of the donation boxes for the building's upkeep and preservation.

I didn't donate. Maybe I should have. I'm not really into Episcopalians or chapels, but I do care about history.

What impressed and surprised me, however, was that, as we were on our way out, my mom stuffed a five dollar bill in one of the donation bins. My dad was looking up at the stained glass windows at the time and I'm pretty sure he didn't see it. But as he walked out, I watched him slip what I'm pretty sure was a ten into the same bin.

Either I misunderstood my parents' stance on donations when I was little, or their stance is evolving. I didn't expect them to contribute because the only organization they trusted to distribute funds ethically and usefully is the church. Apparently I misjudged.

I was actually kind of proud of them for donating. It's useful sometimes to keep my post-Mormon ego in check. I may think I'm right and they're wrong, but they're still better people than I am in a lot of ways. They have a lot more money than I do, but there's no reason I couldn't have spared a couple of bucks. Believing in something that's true (or avoiding belief in something that's false) is far less important than being generous and trying to improve the world around you.

Mormon or not, they have me beat there.

Sunday, July 7, 2013

Saturday, July 6, 2013

Mosiah 6: Nephite Politics

This chapter is kind of an intermediary summary. The King Benjamin speech was a big deal and the Ammon stories that start in the next chapter are a big deal, but this chapter is kind of the current scene fading out.

Holding Fast and Taking Names

At the conclusion of his sermon, King Benjamin "thought it was expedient" to record the names of all the people who had decided to make a covenant with God. According to verse 2, every adult had agreed to make the covenant.

This is dumb—for two reasons. First, come on, Joseph. Again with the entire societies functioning as a hive mind thing? Second, assuming this is an accurate record of historical events, of course so many agreed to the covenant. If you're going to run around like Big Brother taking names of the people who have decided not to be godless sinners, people are going to lie so that their government and their neighbors don't look down on them and treat them differently. Since the tide of public opinion was clearly swaying toward religiosity, it should be no surprise that so many people went along with it. You can sign your name to guarantee your safety because they can't prove you didn't mean it.

A One-Party System

The fact that the Kingship was both a governmental and a spiritual office combined with the fact that the entire society had committed their lives to God and dwelt with "no contention...for the space of three years" (verse 7) makes me think that the political landscape of the ancient Americas was pretty boring.

Hey, I'm going to vote for Mosiah again this year because he's running unopposed and he's the king anyway so we don't get to vote for him and also he's ordained of God so campaigning against him is kind of a sin. But, if anything, I guess he gets my continued stamp of approval this year. Just like last year. And next year. And the year after that.

That's not very American. The LDS romance with the US Constitution and the democratic process is not something they got from their foremost book of scripture.

Mosiah: Survival Expert

The last verse of the chapter relates this oddity:

Holding Fast and Taking Names

At the conclusion of his sermon, King Benjamin "thought it was expedient" to record the names of all the people who had decided to make a covenant with God. According to verse 2, every adult had agreed to make the covenant.

This is dumb—for two reasons. First, come on, Joseph. Again with the entire societies functioning as a hive mind thing? Second, assuming this is an accurate record of historical events, of course so many agreed to the covenant. If you're going to run around like Big Brother taking names of the people who have decided not to be godless sinners, people are going to lie so that their government and their neighbors don't look down on them and treat them differently. Since the tide of public opinion was clearly swaying toward religiosity, it should be no surprise that so many people went along with it. You can sign your name to guarantee your safety because they can't prove you didn't mean it.

A One-Party System

The fact that the Kingship was both a governmental and a spiritual office combined with the fact that the entire society had committed their lives to God and dwelt with "no contention...for the space of three years" (verse 7) makes me think that the political landscape of the ancient Americas was pretty boring.

Hey, I'm going to vote for Mosiah again this year because he's running unopposed and he's the king anyway so we don't get to vote for him and also he's ordained of God so campaigning against him is kind of a sin. But, if anything, I guess he gets my continued stamp of approval this year. Just like last year. And next year. And the year after that.

That's not very American. The LDS romance with the US Constitution and the democratic process is not something they got from their foremost book of scripture.

Mosiah: Survival Expert

The last verse of the chapter relates this oddity:

And king Mosiah did cause his people that they should till the earth. And he also, himself, did till the earth, that thereby...Wait, back up. "Mosiah did cause his people" to cultivate farmland? Seriously? It's been four hundred and seventy-six years since Lehi left Jerusalem and these people still need their king to tell them to plant crops? They must have been really hungry, foraging for nuts and berries in the woods for all those centuries until Mosiah came up with the revolutionary idea to plant their own food.

Friday, July 5, 2013

Thursday, July 4, 2013

My Musical Exit Story

Lately I've been thinking about how my transition from a stalwart Mormon to an even more stalwart non-believer was mirrored by (or influenced by) my choices in music. I feel like, just as so much of my life was a natural progression toward apostasy, so much of my music was a natural progression toward better stuff. My exit story and my music history are intertwined tightly enough that you can't just tell one without telling some of the other.

So let's begin at the beginning.

When I was really little, my understanding of music was limited to church hymns (which I didn't much like as a child) and Disney songs. The Little Mermaid was among my favorite movies. On the rare occasion that my siblings and I put music on the stereo, the most popular choice was one of the Greatest Disney Songs compilations we had. Thus, one of my favorite songs when I was little was "The Ugly Bug Ball."

When I got a little older, I became aware of my Dad's tendency to listen to things that were neither Disney tunes nor church hymns. My dad listened to country western music. Because I idolized my dad as a kid, I wanted to listen to what he listened to, because what he listened to obviously had to be the coolest thing ever. He tried to be careful about what country music he exposed me to, because there's plenty of non-family-friendly country music out there. Instead of the raunchy country and the trucks-beers-and-southern-pride country, he steered me toward the sentimental soft-rock country. And despite my guilty appreciation for Shania Twain's "Man, I Feel Like A Woman," I gravitated toward that same, warm, maudlin, country-with-a-message stuff:

I considered Colin Raye my favorite musician for a while. But now I was heading toward middle school and kids were getting meaner. When people asked me what kind of music I listened to and I told them country, I usually got made fun of--or at least looked down on. I was desperate to find something that sounded less lame than country, but that was still enjoyable and Mormon-appropriate. I remembered a Greatest Hits CD my dad had in his modest collection, and, since I liked it and it was more acceptable than country, I latched onto the Beach Boys:

I knew that modern music was bad and that I shouldn't listen to it, but since my dad listened to the Beach Boys this stuff had to be okay. And I liked it. But since all I had was the one CD, I decided to branch out a little bit. So I listened to my local oldies station in the hopes of discovering music similar to the Beach Boys. (For the record, I thought that the early stuff was the only stuff--I had no knowledge of their output after their surf-rock roots.)

As fate would have it, the oldies station failed only a couple of weeks after I started listening to it. One day, when I tuned my radio to the usual station, it was suddenly classic rock. I tried to find an oldies station to replace it, but, having no luck, I returned to the classic rock station. I figured "classic rock" meant it was still old music, so it probably wasn't evil like the satanic metal music they make today.

To my surprise, I learned that classic rock was actually pretty freakin' awesome. And there were so many artists. I'd stumbled across a treasure trove of musical knowledge to unlock. I listened ravenously for a while, and when that wasn't enough, I started using my parents' tape deck to record of the radio and make my own mixtapes so I didn't have to listen to the stuff I liked less. I discovered Led Zeppelin, Billy Joel, the Who, REO Speedwagon, Kansas, and countless others. Not all of it was great, but enough of it was good enough to keep me hungrily interested.

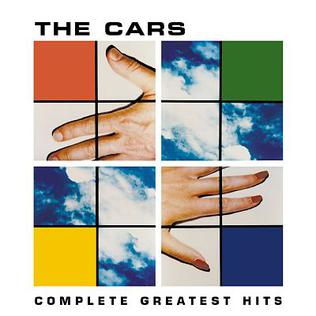

I began looking up some of these bands on the internet to learn more about them. I found a bunch of fan sites for my favorite band. I used my parents' terrible internet connection to stream a Yahoo! Music radio station for my favorite band. And, sometime around my freshman year of high school, I became aware of a new compilation CD of my favorite band. And that's when I tagged along with my mom to Wal-Mart specifically so I could buy my very first compact disc:

I read up on the lyrics and managed to convince myself that this was not evil music because it was recounting the drummer's struggle to free himself from alcoholism. It was heavy and "exciting," but it was a story of a triumphant struggle over sin. Thus I rationalized my growing obsession with Dream Theater--which soon branched out into smaller obsessions with Queensryche, Symphony X, and a small power metal band named Thunderstone. Dream Theater quickly became my new favorite, but I wanted more.

Fueled by my discovery of progressive music and spurred by my twelfth grade English teacher's frequent lectures on the nature of literature and art, I tried to explore as much music as I could, searching for art in music--searching for beautiful sounds that defied label or description, that connected with the emotional fibers of the listener and made philosophical statements instead of just money. It was during this high-brow phase that I found Porcupine Tree.

I'd returned to BYU for my second year instead of going on a mission, and I was entering my almost two-year-period of doubt before I actually left the church. I was confused and angry. Dream Theater and the heavy metal helped me on the anger side, but I didn't have much music to match my confusion. When I found Porcupine Tree, though, I was struck with the band's variety despite its nearly ever-present melancholy. It was a melancholy that I felt I understood and could connect with. When Fear of a Blank Planet came out, that album's depiction of a disconnect between father and son and its bleak atmosphere brought me to tears. The album, despite its frequent criticism of a pill-popping, desensitized generation that I didn't consider myself a part of, had so many moments that felt like they'd been written specifically for me.

It's still my favorite album of all time. It's a masterpiece. Even though I'm in a much different emotional mindset these days, Fear of a Blank Planet still evokes that regretful sadness and still packs the same punch. It's much more musically, lyrically and emotionally complex than Disney or Colin Raye--and it's also something I doubt I'd have ever listened to if I'd remained firm in the faith.

Shortly after I stopped attending church and told my parents I no longer believed, I met my girlfriend. She helped me move out and move on with my life. I told her once about how perfectly Porcupine Tree captured the way I felt about her impact on my life. And because of that conversation, "The Rest Will Flow" has kind of become our song.

I've continued exploring music since then. And I've discovered a broad variety of music over a broad variety of genres. I've enjoyed ignoring the constraints I was taught as a child and finding beauty in unlikely places. I think trading a lifetime of religious rigor for the freedom to enjoy countless musicians' creative and emotional expressions was a good choice. I feel much more like a human being when I listen to Porcupine Tree than I do when I listen to "Praise to the Man" or "High on the Mountain Top."

So here's to good music. And here's to ignoring the religion that taught us not to find it.

So let's begin at the beginning.

When I was really little, my understanding of music was limited to church hymns (which I didn't much like as a child) and Disney songs. The Little Mermaid was among my favorite movies. On the rare occasion that my siblings and I put music on the stereo, the most popular choice was one of the Greatest Disney Songs compilations we had. Thus, one of my favorite songs when I was little was "The Ugly Bug Ball."

As fate would have it, the oldies station failed only a couple of weeks after I started listening to it. One day, when I tuned my radio to the usual station, it was suddenly classic rock. I tried to find an oldies station to replace it, but, having no luck, I returned to the classic rock station. I figured "classic rock" meant it was still old music, so it probably wasn't evil like the satanic metal music they make today.

To my surprise, I learned that classic rock was actually pretty freakin' awesome. And there were so many artists. I'd stumbled across a treasure trove of musical knowledge to unlock. I listened ravenously for a while, and when that wasn't enough, I started using my parents' tape deck to record of the radio and make my own mixtapes so I didn't have to listen to the stuff I liked less. I discovered Led Zeppelin, Billy Joel, the Who, REO Speedwagon, Kansas, and countless others. Not all of it was great, but enough of it was good enough to keep me hungrily interested.

I began looking up some of these bands on the internet to learn more about them. I found a bunch of fan sites for my favorite band. I used my parents' terrible internet connection to stream a Yahoo! Music radio station for my favorite band. And, sometime around my freshman year of high school, I became aware of a new compilation CD of my favorite band. And that's when I tagged along with my mom to Wal-Mart specifically so I could buy my very first compact disc:

As much as I liked Colin Raye and as much as I liked the Beach Boys, the Cars were my first musical love. They were my own. I didn't like them because my dad liked them. I didn't decide to like them so I didn't get made fun of. I liked them because I listened to them by happenstance and thoroughly enjoyed what I heard. I don't listen to Colin Raye anymore. I do occasionally listen to the Beach Boys, but usually their later, more mature stuff. The Cars, however, are still among my favorites. I made sure to see them live during their brief tour in 2011.

I also like to think that the Cars were kind of a metaphor for how my life was at the time. The Cars were once vital, chart-topping rock stars but were now "classic rock" and mostly unknown by my peers. In fifth grade, I was having the time of my life. But since then, my naivete had shrunk and my distaste for the people around me had grown. By the time I became a Cars fan, I was a miserable loner, as unknown in my school as they were. My Mormonism had set me apart from my classmates and I'd shored up the wall myself.

In an effort to remain relevant and not be so out of touch with the other high school kids, I started switching my radio to modern Top 40 music when my classic rock station was on commercial. One of the first current songs I remember hearing was the Black Eyed Peas' "Where Is the Love?" I remember being surprised at the admirable sentiment in the song. Encouraged by a song I didn't much like but that didn't seem evil, I listened some more. And, eventually, I discovered Trapt:

I have a distinct memory of mentioning this song to one of my few friends as we were working on a 10th grade English project together. He gave me kind of a weird look and said, "Wow, I'm surprised you liked that kind of music."

I replied, "Yeah, I kind of was, too." I felt weird, like he'd just told me that I wasn't living up to my Mormon ideals by liking this song--even though I'm sure he didn't even mean to imply that.

This was my first experience with any music that can be considered "heavy" by modern standards. It even has that little scream thing before the chorus. Its lyrics are abrasive and confrontational and not conducive to the Spirit. But I couldn't deny that it was catchy, energetic, melodic, and enjoyable. Though I still considered The Cars to be my favorite band and though I still listened to a lot of classic rock, I started looking into some more modern rock bands. I began listening (without the knowledge of my parents, mostly) to Nickelback, 3 Doors Down, Evanescence, and a few others. And then I heard one song on the radio that made me an instant Breaking Benjamin fan:

I knew of the band because a friend gave me a couple songs ("So Cold" and "Polyamorous," I think), but this song was thirty-seven-and-a-half times better and I couldn't listen to it enough. I think Breaking Benjamin is what finally, irrevocably converted me to heavier music. After this, I began expending more energy toward finding newer, heavier music than toward exploring classic rock. And it was around this time that my dad counselled me against listening to music that "excites" me (see 5. Driving Away the Spirit).

Then I went off to BYU. My RM my freshman year was a guitarist...and a John Petrucci fan. And he is how I became introduced to Dream Theater, my gateway drug to progressive music. I didn't take to Dream Theater as quickly as I did to The Cars, but once they clicked, they clicked in a big way. As Breaking Benjamin was the heaviest music I'd enjoyed to date, Dream Theater struck me as kind of brutal, especially since "The Glass Prison" was one of the first songs of theirs that I heard:

Fueled by my discovery of progressive music and spurred by my twelfth grade English teacher's frequent lectures on the nature of literature and art, I tried to explore as much music as I could, searching for art in music--searching for beautiful sounds that defied label or description, that connected with the emotional fibers of the listener and made philosophical statements instead of just money. It was during this high-brow phase that I found Porcupine Tree.

I'd returned to BYU for my second year instead of going on a mission, and I was entering my almost two-year-period of doubt before I actually left the church. I was confused and angry. Dream Theater and the heavy metal helped me on the anger side, but I didn't have much music to match my confusion. When I found Porcupine Tree, though, I was struck with the band's variety despite its nearly ever-present melancholy. It was a melancholy that I felt I understood and could connect with. When Fear of a Blank Planet came out, that album's depiction of a disconnect between father and son and its bleak atmosphere brought me to tears. The album, despite its frequent criticism of a pill-popping, desensitized generation that I didn't consider myself a part of, had so many moments that felt like they'd been written specifically for me.

It's still my favorite album of all time. It's a masterpiece. Even though I'm in a much different emotional mindset these days, Fear of a Blank Planet still evokes that regretful sadness and still packs the same punch. It's much more musically, lyrically and emotionally complex than Disney or Colin Raye--and it's also something I doubt I'd have ever listened to if I'd remained firm in the faith.

Shortly after I stopped attending church and told my parents I no longer believed, I met my girlfriend. She helped me move out and move on with my life. I told her once about how perfectly Porcupine Tree captured the way I felt about her impact on my life. And because of that conversation, "The Rest Will Flow" has kind of become our song.

So here's to good music. And here's to ignoring the religion that taught us not to find it.

Wednesday, July 3, 2013

Mosiah 5: Mass Conversion

King Benjamin begins to wind down his speechifying...for real this time. He's almost done, I swear.

One More for the List of Things That Just Plain Don't Happen

So apparently, following his address, Benjamin put some feelers out among his peeps to see if they bought all that horrible doctrine of threats and self-flagellation. Joseph Smith would have us believe that the people reacted this way:

When is the last time in recorded history that an entire society was swayed to a particular belief or course of action instantly, unanimously, and passionately based on one address from one authority figure? There are always minority opinions, rebels and dissenters—even when one side should be obviously correct and the other side should be obviously wrong.

But this will be far from Joseph Smith's last mistake along these lines.

Spiritual Incest

Prepare for your mind to be blown by the implication made in verse 7:

So it's not actually incest, of course, but it's more evidence that Joseph Smith was just making this crap up as he went along. It's too bad that he predated Tolkien, because he could have learned a lot from that guy when it came to planning out ridiculous mythology while avoiding continuity errors and plot holes.

Smith hadn't really decided on how the whole God/Jesus thing was going to break down yet, I guess. (In ten chapters, he's going to take a crack at parsing their differences and their relationship and he's going to fail miserably.) Because if he'd hammered out the whole spirit-children-war-in-heaven-older-brothers stuff, then this verse would have been way too strange to be worded this way. There are plenty of options for making the same point without getting entangled in weird celestial familial octopuses.

Pearls of Wisdom

Verse 10 made me chuckle:

One More for the List of Things That Just Plain Don't Happen

So apparently, following his address, Benjamin put some feelers out among his peeps to see if they bought all that horrible doctrine of threats and self-flagellation. Joseph Smith would have us believe that the people reacted this way:

And they all cried with one voice, saying: Yea, we believe all the words which thou has spoken unto us; and also, we know of their surety and truth, because of the Spirit of the Lord, Ominipotent, which has wrought a mighty change in us, or in our hearts, that we have no more disposition to do evil, but to do good continually....and so on and so forth for another three verses. This, of course, is completely unrealistic. People do not behave this way.

When is the last time in recorded history that an entire society was swayed to a particular belief or course of action instantly, unanimously, and passionately based on one address from one authority figure? There are always minority opinions, rebels and dissenters—even when one side should be obviously correct and the other side should be obviously wrong.

But this will be far from Joseph Smith's last mistake along these lines.

Spiritual Incest

Prepare for your mind to be blown by the implication made in verse 7:

And now, because of the covenant which ye have made ye shall be called the children of Christ, his sons, and his daughters; for behold, this day he hath spiritually begotten you; for ye say that your hearts are changed through faith on his name; therefore, ye are born of him and have become his sons and his daughters.King Benjamin's people, then, have become the children of their older brother. They have been begotten by the first begotten of the guy who already begat them. That's pretty messed up.

So it's not actually incest, of course, but it's more evidence that Joseph Smith was just making this crap up as he went along. It's too bad that he predated Tolkien, because he could have learned a lot from that guy when it came to planning out ridiculous mythology while avoiding continuity errors and plot holes.

Smith hadn't really decided on how the whole God/Jesus thing was going to break down yet, I guess. (In ten chapters, he's going to take a crack at parsing their differences and their relationship and he's going to fail miserably.) Because if he'd hammered out the whole spirit-children-war-in-heaven-older-brothers stuff, then this verse would have been way too strange to be worded this way. There are plenty of options for making the same point without getting entangled in weird celestial familial octopuses.

Pearls of Wisdom

Verse 10 made me chuckle:

...whosoever shall not take upon him the name of Christ must be called by some other name

But then I was startled to find a striking teaching a few verses later that I actually agree with. And I think it's related pretty gracefully, without as much of the clunky writing that plagues this usually worthless tome:

For how knoweth a man the master who he has not served, and who is a stranger unto him, and is far from the thoughts and intents of his heart?

So my first thought, after the initial shock of reading something in the Book of Mormon that I actually liked, was this must be plagiarized! I did some quick Googling in the hopes of confirming my suspicion, and I learned that some of this verse might be plagiarized, but it's the last few words and not the core concept. So congratulations, Joseph. You're on the board with one run. But we're somewhere in the bottom of the third inning here and you're still down by about 1,346. So don't get your hopes up.

Incidentally, I'd be interested to learn if anybody else has figured out where that possibly legitimate pearl of wisdom in Mosiah 5:13 actually came from.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)